A Wall That Once Spoke

I. Maria (Maro)

Sis (Flavias), Cilicia

2nd–4th century AD

Roman rule · Greek spoken · rural settlement near a main road

Maria wakes up before the day really starts.

The stone floor is cold. She pulls her shawl tighter and steps into the courtyard. Water, hands, face. Same order, every morning. Not because someone told her to — because this is how mornings work.

Life is repetitive, but not empty.

She grinds barley. The sound mixes with goats, children, metal somewhere nearby. Greek is spoken, but not the kind written in books. It’s mixed, bent, practical. Latin words come with officials, other sounds with traders. Nobody thinks about it. Language is just what gets things done.

People call Maria hosia — righteous.

Not because she talks about faith, but because she shows up. She keeps promises. She brings food to the widow. She remembers graves when others forget.

When she gets sick, she doesn’t make a thing of it. She keeps going. Until one day she doesn’t.

They bury her near the road. Someone who knows how to carve, but not beautifully, cuts her name into stone. No long sentences. No poetry.

Just what matters:

Her name.

What kind of person she was.

That she died.

Enough for anyone passing by to understand.

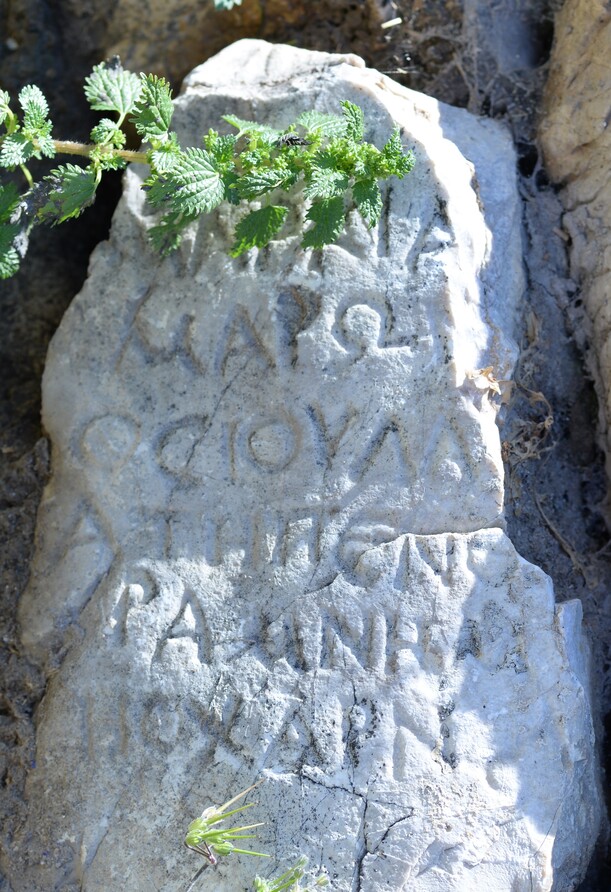

What was carved:

[Μ]ΑΡΙΑ

ΜΑΡΩ

ὉΣΙΟΥ

ΑΠΕΘΝΗ

ΠΡΟ ΜΗΝΩΝ

Ἡ ΧΑΡΝ[Η]

II. The Wall

Kozan, Turkey

Early 21st century

Modern nation-state · Turkish spoken · private rural property

The stone is heavy, but it’s good stone.

Mehmet presses it into the yard wall and wipes his forehead. Old stones are always better. They don’t crack easily. They’ve already proven themselves.

He doesn’t read what’s on it.

The letters aren’t his. He knows Latin letters, some Arabic from prayers. These belong to no language he uses. To him, they’re just lines and curves. Texture.

Life happens around the wall.

A hose leans against it.

A ball hits it and bounces back.

Peppers dry in the sun, hung from nails driven between old cuts.

Sometimes the light hits the stone at an angle and the letters stand out. He looks at them for a second. Wonders who made them.

Probably someone important, he thinks. Old things usually are.

Then dinner is ready.

And that’s the end of it.

For Mehmet, the stone matters because it works.

It holds the soil.

It marks a boundary.

It lasts.

The name on it doesn’t change that.

What it once meant:

“Maria (Maro), a righteous woman, died some months ago.”

III. What Changed

Maria lived in a time when objects were expected to speak.

A stone was trusted to carry meaning forward.

Mehmet lives in a time when objects are expected to function.

Meaning lives somewhere else now — phones, photos, memory that refreshes itself.

Neither way is better.

They’re just different.

The same stone once said:

A good person lived here.

Now it says:

This wall stands.

Everything you think will last — everything you believe carries your values — can be understood differently by the people who come after you. Even if they live in the same place. Even if they use the same things.

The stone stayed.

What we expected it to say didn’t.

And maybe that’s the real lesson:

not everything meant to be permanent knows how to explain itself forever.